I have not seen the design for the new Hayward Field stadium, therefore I cannot offer an opinion. I do know there is some controversy, which is only natural with such a beloved place. I think it’s great that people care so much.

I appreciate that this is a sensitive topic that brings forth strong emotions. Acknowledging that, I would like to share a few stories about what Hayward Field means to me and how I am looking at the project. To me, the spirit of the place is best captured by a series of short vignettes, all experienced within a few short weeks during my freshman year.

The Men and Women of Oregon

On April 2, 1977, I competed in my first University of Oregon dual meet, one of a fresh crop of newbie “Men of Oregon.” Oregon dual meets were legendary, and I was so proud to wear that lime-green Oregon singlet, hand-sewn by Mrs. Martha McChesney, the mother of two of my teammates. A nice crowd showed up for our meet against the Washington Huskies, but there was angst in the air because the track program was trying something new—staging the first coed dual meet with the UO’s men’s and women’s teams competing at the same time. A lot of “old timers” didn’t think it made sense. They didn’t like it. They thought the women would devalue the Oregon dual meet experience; that they weren’t good enough. Like all dual meets, the meet started with the men’s 4 x 100 relay. The women followed. Event by event, this new format rolled out.

I don’t know at what point of the day it happened, how many events in, but I was lucky enough to witness it. The Oregon women’s team, with their athleticism, power, and drive, quickly won over the crowd. They were every bit the athletes that the men were and the Hayward fans loved it. On that day, I was both a fan and an athlete, and I loved it, too. I learned something that day—that an openness to change can make a great thing even better. Oregon track and field entered a new and better era that day in 1977.

The Victory Lap

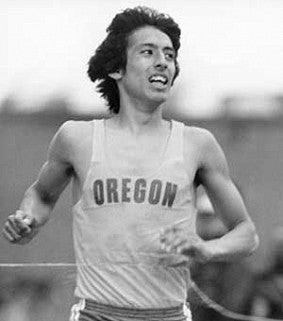

That day was also my first Oregon dual meet. I ran the 5,000-meter—Pre’s event. It was a close race, but with 330 yards to go, right in front of the east grandstands, I took off, winning in a time of 13:53. One year later, that same side of the grandstands would cheer me along at the NCAA Championships.

As I walked off the track, a teammate grabbed me and said, “You have to take a victory lap.” I said, “I’m not taking a victory lap.” I was a shy kid, raised in a modest, working-class Mexican American home. I just didn’t do those types of things. So, I just shook my head and left to cool down.

After the meet, as I was walking off the track, a kind, gentle older man in the stands called me over. He said, “You know, at Hayward Field, when someone wins a race, they take a victory lap. It’s not so much for the winner, it’s for the fans. They just want to show you how much they appreciate your performance. They love this sport and want to honor you.” I looked at him, embarrassed, and just nodded. He then said as I was walking away, “Son, if you’re ever lucky enough to win another race at Hayward, do yourself a favor and take a victory lap.” After that race, I was fortunate enough to win a few more times at Hayward Field and never again skipped the victory lap. Each time, my love and affection for the place grew ever deeper.

In art, there is a concept called “the beholder’s share.” In short, it means that no work of art is complete until it is experienced by the viewer—the emotional and intellectual engagement of those who experience it is an intrinsic part of the art itself. The same concept holds true for the magic that happens at Hayward. The victor, the venue, and especially the fans create an experience like no other. Whether it was Pre beating Shorter, Salazar’s duel with Rono, Wheating’s Olympic Trials 800, or English Gardner’s 100, those unforgettable victories framed by our venerable old stadium would not have been the same without the wonderful, knowledgeable, and passionate fans of Hayward Field. The frame may change, but the heart and soul of the Oregon track-and-field fan will remain forever.

Meeting the Man

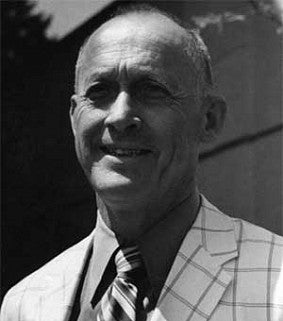

Bill Bowerman

One morning that same spring of 1977, our team of distance runners was warming up on the track at Hayward Field. It was a foggy, misty Oregon day, where you couldn’t see more than 50 feet in front of you but could somehow still see the silhouette of an orange sun. As we entered the turn, just past the finish line, we could see the outline of a man on the curve of the track, on his knees, mixing cement next to a pile of stones. As we got closer, someone said, “Wow, that’s Bowerman.” Stone by stone, he was repairing the drinking fountain that still adorns the south curve of the track.

Awestruck, every single runner walked up slowly, shaking his hand and introducing himself. Although Bill Bowerman was a legend and a man with resources, when I first met him he was on his hands and knees, still serving the athletes of Hayward Field. Along with the other great Bills (Hayward and Dellinger), he “built” Hayward Field into the iconic venue it became. I did not meet Bowerman again for many years, but his unpretentious manner and love for Hayward Field stayed with me. Years later, as I became more of a student of Oregon’s legendary track program, I realized that Hayward, Bowerman, and Dellinger were all innovators, always looking toward the future, trying to figure out ways to improve performance. They were also very real, very Oregonian, never standing on ceremony and always insisting you address them by their first name.

The Jogathon

That same year, we all were required to help raise money for a new track surface by participating in a “jogathon”—running as many laps as we could in one hour for which sponsors would give us a dollar a lap. After the event, they told me I had set a new collegiate record for the hour run, but what I remember most about that jogathon was how hard it was to ask my father and uncles, all steelworkers back in Indiana, to send the UO almost $60 each to help pay for the new Hayward Field track. It was a different era back then.

Hayward Field – The Future

Last week, I was talking to my old coach, Bill Dellinger. At the close of our conversation, I asked him how he felt about the new Hayward Field project. Although speech is sometimes difficult for him after his stroke, his answer was clear. “I think it’s good. It’s time.” I was surprised by his answer, but when I think about the three Bills—Hayward, Bowerman, and Dellinger—it made sense. They were always thinking about the future.

Only time will tell if the new stadium is able to capture the magic of the old Hayward. What I do know is that it won’t have the iconic east grandstands, but I’m alright with that. Although I think that Hayward Field is one of the most beautiful stadiums in the world, I’m also confident that the spirit of Hayward will continue to live. To me, the heritage of Hayward Field is less about the timber and cement stands that surround the track. It’s more about the spirit and enthusiasm of all those who have trained, competed, and cheered there over the years. In thinking about the new Hayward Field, what matters most are not these old memories, but what it will mean to kids like my two-year old granddaughter. If they get it right, little kids like Canela Chapa will experience that same old magic, and the “new” Hayward Field will simply be their Hayward Field.

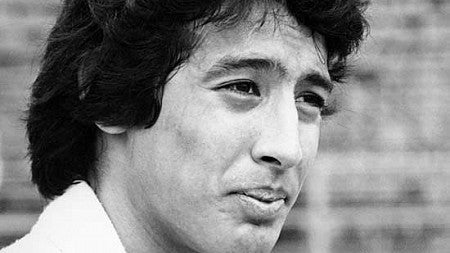

Rudy Chapa

Rudy Chapa is a former member of the UO Board of Trustees. He graduated from the University of Oregon in 1981 and joined Nike Inc., in 1992, where he ultimately served as the global vice president for sports marketing and later as vice president of Nike.com. He left in 2001 to found his own investment firm, Quixote Investment.

Chapa was a six-time All American in cross country and track and a member of Oregon's 1977 national champion cross country team. In 1978 he won the NCAA championship in 5,000 meters while running in front of his home crowd at Hayward Field. The next year he broke the American Record in the 3,000 meters at Hayward Field as well, running a time of 7:37.7 to break Steve Prefontaine's record by five seconds. On May 28, 1981, Chapa joined the sub 4:00 mile club when he ran a 3:57.04 mile in Eugene.